A figure is a named, choreographed movement or sequence of steps. This comes to us from dance traditions of the British Isles, where dancers would work together to create patterns of position and movement. Compared to ballet training today, a figure is larger than a step and smaller than an enchainment (“combination”) — and it has a permanent name! Dancers within a tradition would learn a number of commonly understood figures and be able to execute them on the spot, thereby enabling dance performance based on a caller telling dancers which figure to execute next. A Figure Dance is therefore a dance constructed of a sequence of figures. Figure Dancing traditions remain alive and well today.

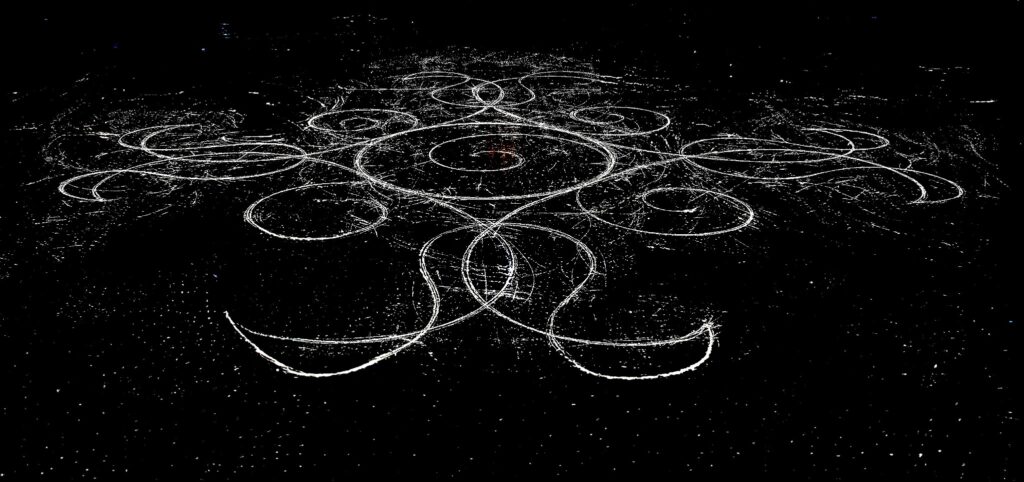

Skating for art and pleasure was first developed in England and Scotland, where people began adapting their dance traditions to the ice. Documenting dances by drawing diagrams showing where dancers move on the floor was already standard practice; but skating figures on ice became self documenting because of the tracings left behind. Thus “figure” came to have a dual meaning, referring both to the named, choreographed sequence of steps, as well as visual pattern left on the ice upon completion of the figure. By the 1890’s, this developed into an elaborate visual art from with the ice as a canvas, with skating “scenes” in North America, England and Vienna.

Figures, Art and Sport

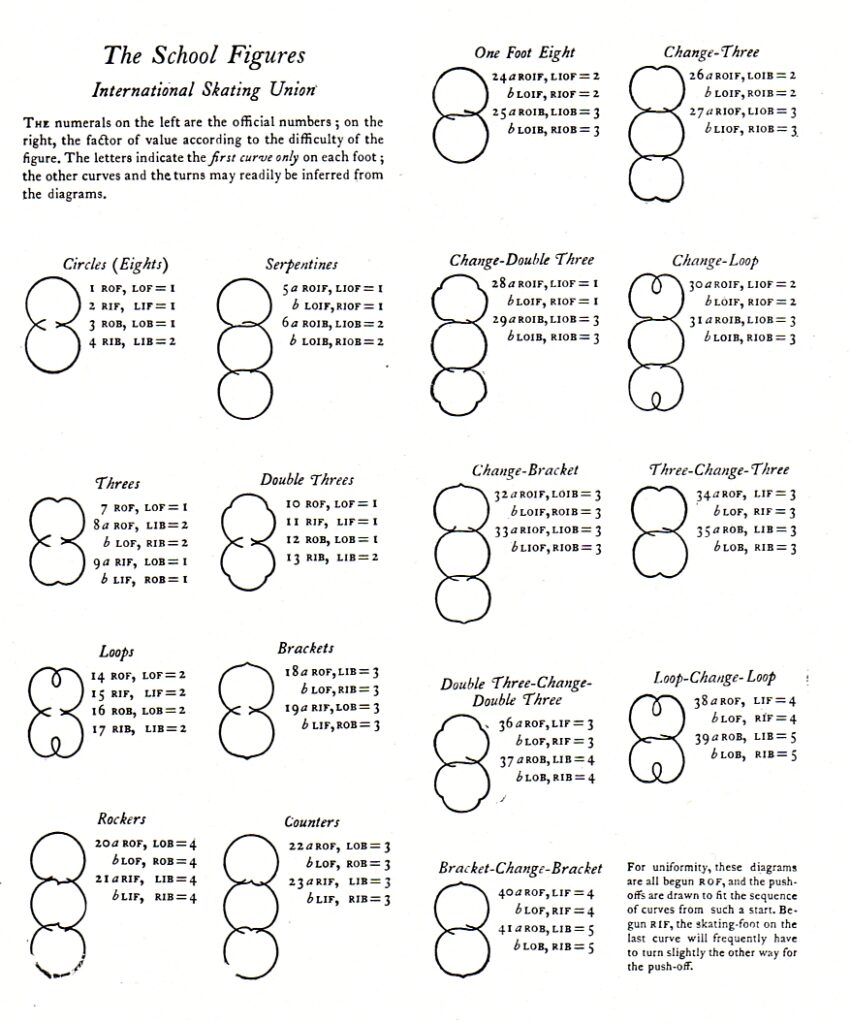

Throughout the 19th century skating was consistently referred to as an art; and skaters would hold contest when they got together. This began to change in the 1890’s with a concerted effort to create a sport and the founding of the International Skating Union (ISU) with a delegation including skaters from around Europe (but no one from North America). In 1897, British members of the delegation provided a simplified and standardized set of figures to serve the needs of judging and competition. This limited set of figures came to be known as School Figures (Fundamental Figures) and was commonly practiced worldwide until the ISU abolished them in 1990. In this new sport, figures were no longer a visual art, but rather a training aid for the new International Style of free skating. In fact, they were described as a “grammar of skating,” used to practice the basic principles of skating, and now involved only circles and loops. Figures involving beaks, cross cuts, pirouettes and other shapes were not included.

From Irving Brokaw, The Art of Skating, 1915.

Large Figures, Small Figures… and Loops!

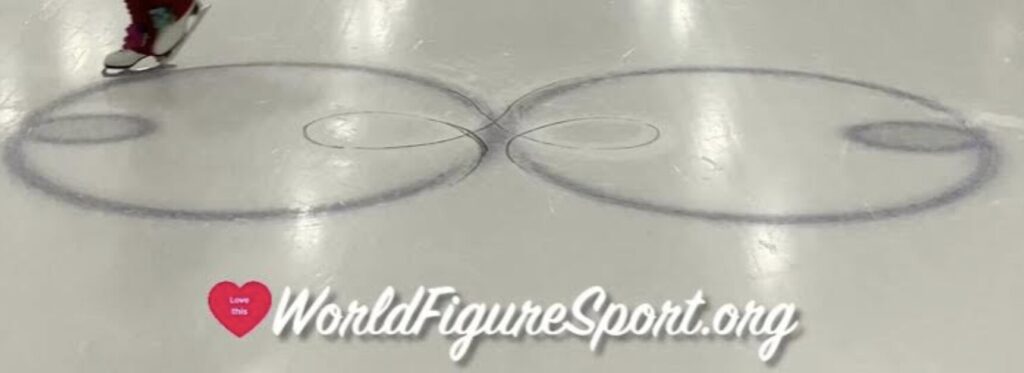

Figures come in two general sizes, large and small. Large figures such the ISU Figures descended from English Style skating. They involve larger circles and time to balance between “action points.” North America had harsher weather and more snow, and skating required that one shovel off an area to practice. North Americans had less space for larger figures and hence specialized in smaller (and fancier) figures such as the Maltese Cross and Swiss S.

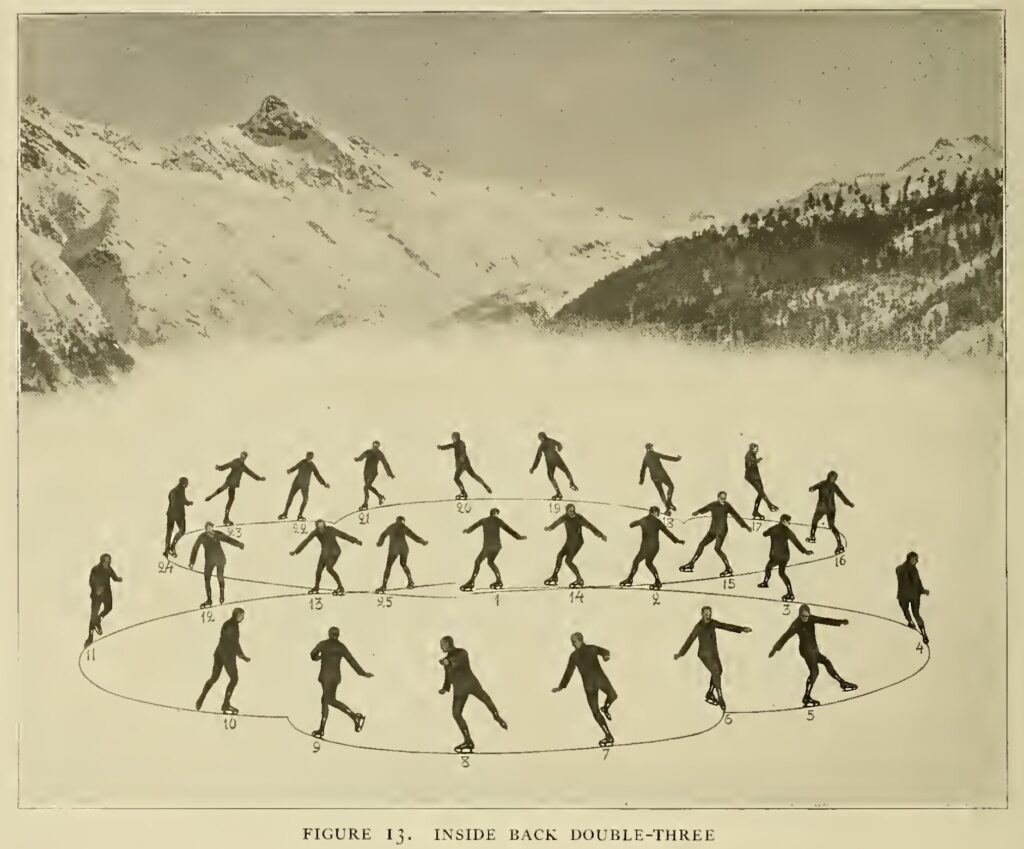

Bror Meyer, Skating with Bror Meyer, 1921

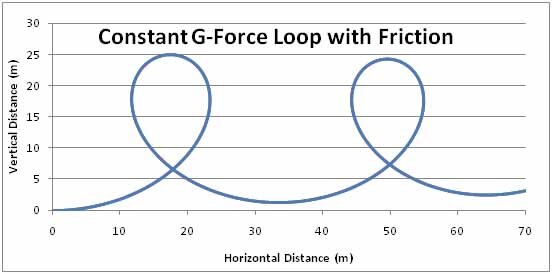

Most importantly, the Loop was of North American mid-19th century origin. The beautiful and mysterious shape of the loop is what happens when the skater minimizes jerk and executes acceleration in and out of the loop in the smoothest way possible. This shape was first discovered by the mathematician Leonhard Euler as the Euler Spiral or Clothed Loop, and then later discovered experientally by North American figure skaters. In the 20th Century, this beautiful teardrop shape found additional use in roller coasters and smooth transitions for railroads and highways. Long live the Loop!

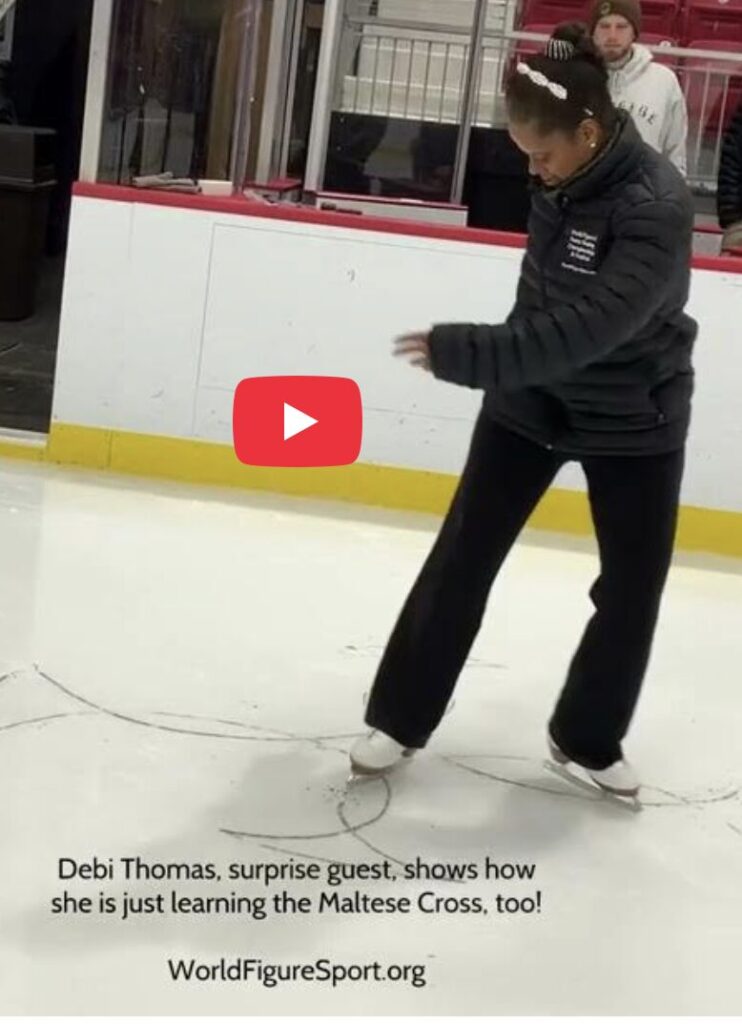

Debi Thomas Practicing the Maltese Cross. See here for more. By permission of World Figure Sport.

Loops may be executed in many ways, see here for some devilishly difficult Butterly Loops. By permission of World Figure Sport.

See here for Swiss S. By permission of World Figure Sport.

Why are Figures Great?

- A complex figure traced over itself 6 times with centimeter precision is a beautiful and virtuosic testament to what is humanly possible.

- Each figure is a puzzle: simple to describe, easy to evaluate, difficult to execute. Each figure becomes our teacher. As we strive to make our bodies glide around the ice in perfect circles, we delve inside ourselves into a thousand fascinating things happening inside. Thus figures both help us deepen our relationship with our body as well.

- Difficult moves are best practiced within a figure constructed for the purpose — preferably one that takes only a few seconds to execute, contains appropriate context for the move, and can be repeated immediately upon completion. This is the most efficient way to teach our bodies something new.

- If we have enough figures under our belt, we can put together a free skate program quickly.

- Although figures take decades to master — if ever — they require no special physical abilities — just balance, control and patience. And yet, only one person has ever received a “perfect” 6.0 score on a figure in competition (Shepherd Clark, first in 2017).

- Figures are rarely a source of injury; in fact, their practice is known to decrease the chance of injury in free skating and improve upper body strength and stability. In a world increasingly crowded with challenging (and dangerous) extreme sports, figures offer an alternative approach to challenge.

- We can practice and improve our figures for as long as we live, and either perfect them or die trying. The benefits of balance training in our senior years are well documented.

- Figures are magical, defying the laws of physics. We learn to skate endlessly on one foot without losing speed, and also how to stop and reverse direction like a car doing a K-turn — on ice skates!

- We can impress our friends laying down cool tracings on the ice, giving off cool skateboard vibes while executing the cross cuts.

- We contemplate how skating is made of the two most perfect shapes: the circle and the Euler spiral (loop).

- Figures are fun!

- Figures are beautiful!