This introduction is written for anyone, whether skating artist or spectator, who wishes to learn more about the art of Figure & Fancy Skating. If you wish to learn and perform this art yourself, resources are available to get you started and help you along the way! Please contact the World Figure Sport Society by phone, text or WhatsApp to get swift replies at: 518.304.3029

From Figure Dancing to Figure Artwork

In the context of dance, a figure is a named pattern of movement that is bigger than a step and smaller than a phrase. Figures were a widespread feature of Western social dances in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, and typically involved multiple dancers creating formations and patterns (Aldrich 1998). Dances were documented using a variety of notations, which would graphically represent the ballroom floor and the ways dancers would travel through space on that floor. Figures remain a feature of popular group social dances derived from these older forms, including Contradancing, Irish Dancing and American Square Dancing. Common figures taught in Irish Ceili dance today include “Advance and Retire,” “Figure of Eight,” “Hands Round Four,” etc. Irish step dances are often built around a single ”figure”, which alternates with ”steps”, similar to the repeating theme in a musical ”Rondo”. Dances constructed in this way are called ”figure dances” (O’Keeffe 1914). Some forms of figure dancing, such as Square Dancing, feature a caller who tells the dancers which figure to perform next; dancers are expected to learn a shared vocabulary of figures and perform them upon request by the caller.

The art of ice skating for pleasure was first developed by English upper classes in the 18th century (Jones 1780), who brought their dance forms onto frozen ponds. In what came to be known as ”figure-skating” or later, ”English Style Skating” (Cobb 1913), dances on ice were performed by multiple skaters in formations, executing figures in response to a caller. As with other dance forms of the time, the figures involved in figure-skating were documented by drawing a pattern on a page representing the skating surface (Montagu 1883). Figure-skating was distinguished from “plain skating,” in which people just skate forward and do not execute any figures.

As the art of figure-skating gained popularity beyond England, participants in North America and Continental Europe adapted the art to their own cultures and circumstances. In North America due to different climate (Meagher 1895) the large expanses of lake ice required for English Style Skating were not available, and skating artists focused instead on figures requiring less space. Unique among figure dance forms, figure-skating left behind tracings on black pond ice, which people could view upon completion. Thus the term figure thus came to have a dual meaning as both a named sequence of movements, and the tracing left on the ice when executing the figure, in this way figure-skating became a visual art as well as a performing art.

By the end of the 19th Century, there were three major figure-skating “scenes” worldwide in England, North America and Continental Europe (Vienna), each with its own approach and stylistic preferences. English Style Skating emphasized large high-speed group (“combined”) figures with upright comportment. North Americans were creating a dizzying array of complex and challenging figure artwork (Meagher 1919). And in Vienna, local Waltz, Ländler and other folk dances were adapted to the ice and performed to music, as originally inspired by the American ballet dancer Jackson Haines. Skaters were aware of what others were doing elsewhere, and had opinions about them. Many skaters outside of England felt English Style Skating was too rigid and upright, and its emphasis on uniformity of carriage prevented individual expression. For North American skaters, the main criticism was that the free leg and body motions required to execute advanced techniques such as cross cuts, similar to the look of skateboarders or snowboards today, was not graceful enough and could not properly be considered as skating art. Nevertheless, there was plenty of crossover and individuals would choose how they wished to skate. World Champion Ulrich Salchow was famous for his star figure (Meagher 1919); and the first and only Olympic Special Figure event was won by Nikolai Panin of Russia.

Although all types of skating above were described as “figure” skating — skating based around named patterns of movements — different kinds of figures were understood differently. Figures to place, such as those in English Style Skating or those used to create figures artwork, require the skater return repeatedly to a fixed “center” and retrace the same figure to varying degrees of precision, whereas figures in the field or free skating did not return to a center. Flying figures, whether to place or in the field, involved going airborne while continuing the figure on the ground both before and after the airborne segment. Axel Paulsen’s famous jump was first demonstrated at the 1882 Great International Skating Tournament in Vienna as a flying figure in the field.

Here are some excellent examples of figure artwork:

- The Maltese Cross, was known and documented in the 19th century, but had become nearly extinct by 2015. It is now widely taught at World Figure Sport events. Anne Bennet holds the Maltese Cross world record, having skated 29 consecutive patterns of it over 6 minutes, all one one foot!

- Beacom Blossom (Gary Beacom, 2016) (and here too) uses almost every technique taught in the ISU Figures (see below), all in one figure, a true tour de force! It is also an excellent example of continuous skating: Mr. Beacom stays on one foot for extended periods, building and maintaining speed through skilled use of 3-turns, loops and change-fo-edges.

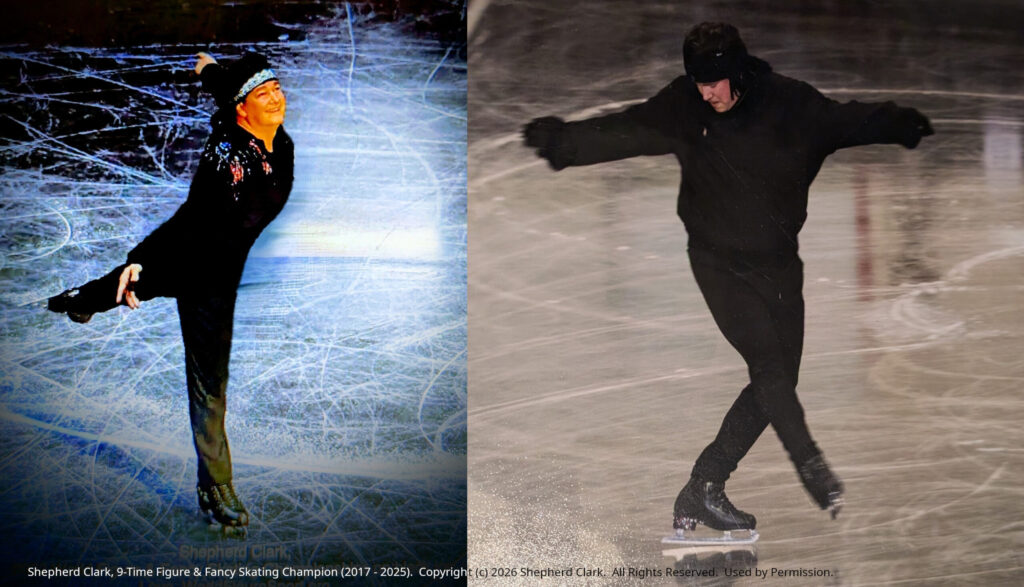

- Shepherd’s Spiral (Shepherd Clark, 2024).

Fancy Skating

By the 1890’s, skaters particularly in North America were practicing the art of Figure & Fancy Skating (Meager 1895, Grosvenor 1896). As described by Grosvenor, it consisted of two parts: figure artwork (described above), and fancy skating. Fancy skating, in contrast to plain skating, is a form of free skating based on two principles: bringing figures to place into the field and thus adapting them for free skating; and the art of continuous skating, or executing multiple things on one foot while building / maintaining speed by pushing against the ice with only one foot. As practiced today, fancy skating is an athletic art, or dance on ice, in which one or more skating artists present an original choreographed composition set to music. Fancy skating includes all types of figures. Its purpose is to unite the skating artists’ profound technical and artistic mastery of fine, performing, decorative and recording arts, thereby transcending oneself and the audience. Every edge, extension, nuance, and expression should flow together on the ice originating solely from the musical necessity with world class skating technique and riveting choreography.

Because of the multi-dimensional nature of the art, fancy skating can and does vary widely, allowing every skating artist to create their own personal style. Here are some excellent examples of fancy skating:

- John Curry, After All, 1980 (choreographed by Twyla Tharp). The first movement is constructed entirely of figures to place that were in common practice at the time, set to music and smoothly executed. With its upright posture and focus on precision, the overall dance maintains a classical aesthetic.

- Sarah Jo Damron-Brown, 2024. Presenting a more romantic aesthetic, Ms. Brown demonstrates excellent continues skating by executing multiple figures on one foot. Her attention to the music creates the transcendent illusion that she is creating the music, not merely responding to it.

Sportification and the Loss of Diversity

Art and sport are social constructs, and we classify activities into one or both categories based on the attitudes and goals of the people doing them. Painting and music are arts, football is a sport, and chess is also a sport. The defining difference is arts are pursued primarily for aesthetic ends, whereas sports involve contests, competitions and rules to determine winners. This is not to be confused with athletic involvement. Ballet is extremely difficult and highly athletic — it has been endlessly compared with American football — but that does not make it sport, in fact ballet dancers consider it to be 100% art. Similarly, chess is not particularly athletic but is in fact a sport with a governing body that sets the rules and decides who gets to qualify to play in which tournaments.

Critical to any sport is a governing body, which sets the rules for everyone in a top-down manner; in contrast arts have no overall rules and can at times work at the grass roots. Sports are explicitly tied to nationalist politics; art is historically used for social protest. Arts code liberal, sports code conservative. Arts diversify over time as new artists take them in new directions; sports become more uniform as athletes learn what scores the best and copy each other.

Through the end of the 19th Century, figure-skating was universally described as an art, with diverse approaches in different parts of the world. There were skating competitions, just as there are piano competitions today, but it was still an art pursued primarily for its aesthetic and social value. Moreover, the competitions were quite different. A skater skilled at winning North American competitions might not do so well in Vienna, due to different skills being practiced and valued. And North American competitions were notorious for having long lists of figures that might be competed at any given event, making it hard for skaters to prepare.

This began to change in the 1890’s, with the modern concept of a sport being developed. The International Skating Union (ISU) was formed in 1892 as the International governing body for the new sport of figure-skating, and standardization was their first task. They chose to base the new sport on the free-flowing audience-friendly Viennese approach to skating, which they now called the International Style. In 1897 they asked the. British delegation to produce a standardized / simplified set of figures. This became the set of figures that were used for training and competition over the next 90 years until the ISU dropped them around the year 1990. At the time they were described as a grammar of skating, i.e. they included all the technique needed to learn how to skate the International Style. Notably, they did not included cross-cuts, which more a North American thing and many en Europe felt were not graceful. In fact, No North Americans were on the ISU committee.

Beginning the turn of the. Century, a handful of skaters began to promote the International Style in North America, including Irving Brokaw and George H. Browne. North Americans did not adopt the International style en mass at first, and in fact had their own competition governing body called NASA. However as European and English skaters standardized on it, North Americans found themselves unable to participate meaningfully in this new sport. The death knell for figure artwork came in 1921 when the United States Figure Skating Association was founded as the ISU-affiliated governing body for the United States. After that, American skaters adopted the International Style en mass and the “old ways” largely died out within a decade or two; although the Cambridge Skating Club was offering tests in figure artwork as late as 1948. Similarly, English Style Skating slowly lost popularity in the UK through the 20th Century. Information about it was removed from British skating materials around 1990, and as of 2025 there is only one remaining club (The Royal Skating Club) and a handful of people who continue to practice this foundational form of figure dancing on ice.

And thus in the span of 30 years, sport replaced art. In the process, most of the diversity that existed in 1890 and was documented in numerous books was abandoned. English Style Skating was reduced to a set of training exercises on circles. Figure artwork was abandoned after the 1908 Olympics, and the the cross cuts that made it possible were no longer taught. Even most of the Viennese skating scene, as documented in Spuren auf dem Eise (1892), did not make it into the International Style, being practiced today only in Vienna and preserved as UNESCO Heritage. Other forms of figure-skating, such as hand-in-hand skating have been completely lost.

Throughout the 20th Century, the sport of figure skating, as defined by the ISU, maintained a balance between art and sport. Although much skating knowledge was abandoned, other skating knowledge was developed, for example most of the jumps and spins popular today. However, videos and judging manuals show a loss of diversity since the 1950’s with many jumps having been eliminated from the scoring sheets. This is most likely due to the development of double, triple and quadruple jumps and the cultural value placed on them: jumps not amenable to multiples were deprecated and discarded, leaving us with only six competition-worthy jumps today.

Two changes in the 1990’s accelerated the loss of diversity and disrupted the balance between art and sport: the abolishment of ISU figures in competition and implementation of IJS scoring. Skaters stopped training figures soon after figure competitions were eliminated; and this is widely seen as having degraded the overall level of training. Moreover, IJS scoring created a system in which multiple jumps are so highly valued that not much else matters. Much free skating today has devolved into a “jumping contest”: difficult, highly technical and often dangerous, but not art. Individual skaters can and do demonstrate artistry in their movement; but it is almost impossible to create actual art with choreography designed to win a high IJS score. It is hard to imagine how a new Torvill and Dean, and the art they created with Bolero and their Paso Doble, could happen in today’s sport environment.

Figure & Fancy Skating Today

The World Figure Sport Society (WFS) was founded in 2015 to preserve, promote and even resurrect skating knowledge. It is today the primary promoter of the art of Figure & Fancy Skating, presenting the World’s Greatest Skating Artists its flagship World Championship on Black Ice every October, with a vibrant mix of art, sport and community. WFS also provides training resources, supporting the development of current and future skating artists worldwide. Prospective skating artists should contact WFS to get started.

Figure & Fancy Skating is not the only skating art alive today. Art thrives on diversity, and no organization or single style of skating can encompass all of what skating art is or could be today. Other skating art organizations and movements include:

- Professional performance companies such as Ice Theatre of New York, American Ice Theatre and Ice Dance International.

- The Contemporary Skating Alliance is a non-profit international organisation of companies and individuals supporting the exploration and evolution of contemporary skating and movement on ice.

- The Royal Skating Club is the last remaining club keeping the practice of English Style Skating alive. Figure-skating technique was developed by English skating artists, and this club possess valuable archives on the foundational history of figure-skating.

- Freestyle Ice Skating is a skating art, performed in hockey skates, that channels the aesthetics of breakdancing, snowboarding and other extreme sports. It was first created around the year 2010 and has built a loose global community, mostly in Europe, using the Internet and video sharing. An annual gathering is held in Vienna or Budapest in February.

References

- Aldrich, Elizabeth (1998). Western Social Dance: An Overview of the Collection: An American Ballroom Companion: Dance Instruction Manuals, ca. 1490 to 1920, Library of Congress Digital Collections

- Cobb, Humphry H. (1913). “Figure Skating in the English Style,” Evleigh Nash, London

- Grosvenor, Algernon (1896). “Fancy and Figure Skating”, The New Review Vol. 14, Issue 81 p 152-161

- Jones, Robert (1780). “A Treatise on Skating”, London

- Koepwe, C (1892). “Spuren auf dem Eise: die Entwicklung des Eislaufes auf der Bahn des Wiener Eislauf-Vereines (The development of skating with the Vienna Ice Skating Association)” A. Hölder, Vienna

- Montagu, S. F., Monier-Williams, B. A. (1883). “Combined Figure Skating”, ”Horace Cox”, London

- Meagher, George A (1895), “Figure and Fancy Skating,” ”Bliss, Sands and Foster”, London

- Meagher, George A (1919), “Guide to Artistic Skating” ”T.C. & E.C. Jack, Ltd”, Edinburgh

- O’Keeffe, J G and O’Brien, Art (1914). “A Handbook of Irish Dances“, M.h. Gill & Sone, Ltd, Dublin, Ireland